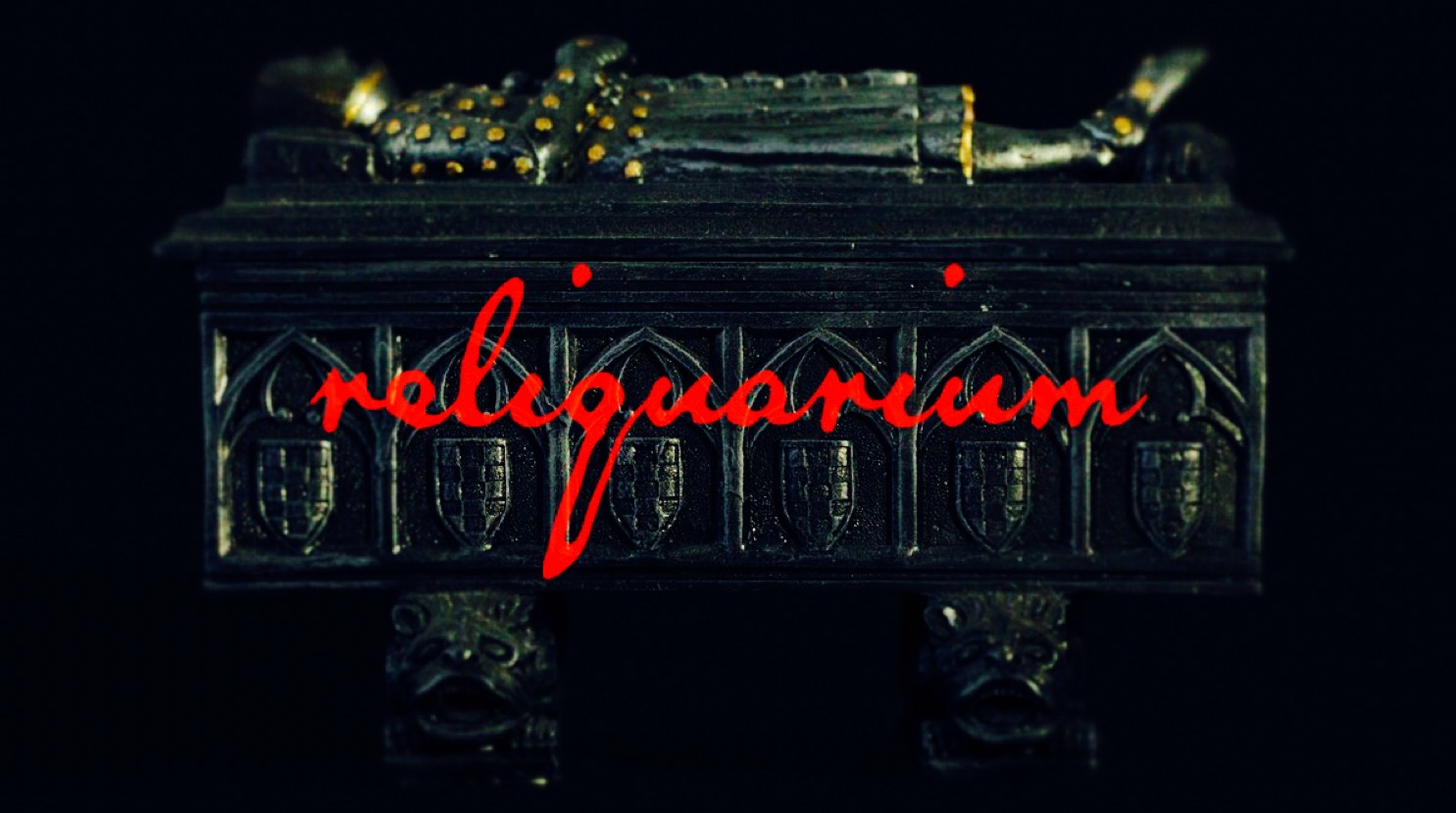

On Reliquarium: Part One

by Kemper Crabb

History is a corkscrew: a spiral, really. It seems like it moves forward in a line (and it does, sort of), but really it has these ups and downs, these punctuated rhythms which are like counter-steps in a complicated circle-dance. The history of the Church is not only not immune to this, but in many ways is actually paradigmatic for everyone's ongoing history, Christian or not, encompassing individuals, families, nations, cultures, etc. And culture is what I'm primarily thinking of and addressing here.

Having been a musician all my life (and a minister for most of that time), I've been much involved with the music of the Church (especially its worship music). Those who are familiar with my recordings and live performances either associate me with rock and pop music (ArkAngel, Hope of Glory, Atomic Opera, RadioHalo, Caedmon's Call) or with Early music and folk (the Vigil, A Medieval Christmas, Downe In Yon Forrest), and, considering my musical output, that's easily understandable. I was involved in the first wave of what became CCM music (which didn't really exist when we started during the Jesus Movement around 1970), and, because of that, I've always been involved with contemporary worship music, and still am. But I grew up singing hymns.

From the earliest times I remember, I sang hymns in worship services, especially after I embraced Christ as my Savior at 11 years of age. The hymns, of course, took on deep experiential and emotional roots within my awareness after my conversion. As I grew older, I learned a good deal about the hymnists who composed these songs which dominated my youth. I was especially impressed with the lives of four of them:

-Fanny Crosby, blinded accidentally soon after her birth, nonetheless became the most prolific hymnist who's ever lived, becoming a skilled multi-instrumentalist (including guitar, a very unusual instrument for a woman of her time), a friend to presidents, the first woman ever to address the United States Senate, and much more.

-Charles Wesley, brother to John Wesley, and one of the progenitors of the First Great Awakening, was subjected to continued ecclesiastical persecution and physical threats following his conversion and commitment to public preaching, began to write hundreds of hymns of elegance and eloquent theological poetry.

-Charlotte Eliot, a member of the Clapham Sect, William Wilberforce's Evangelical group committed to Biblical social change, contracted a mysterious debilitating disease which forced her to lead much of her life as a semi-invalid, but led her to pen some of the most beloved hymns in the English language.

-George Whitfield suffered enervating depression all of his life, attempting suicide multiple times, yet rose to become one of his time's most respected poets (even considered for the post of poet-laureate of England) and developed a close friendship with John Newton, publishing with him some of the greatest hymns ever penned.

All of these men and women faced tremendous challenges and yet mastered and utilized to great effect the artistic expressions of their time to provide a medium of common and participatory faith which worshippers ever since have used in worship.

As I began to write worship songs myself, I gradually became more and more interested in how these various hymnists approached composing their songs, and realized that, though they self-consciously embraced the contemporary lyrical and instrumental forms of their day, they were also deeply informed by the musical traditions of the Church in the centuries before them. This led me to realize that, just as they were informed by past musical practices to compose their songs, so was I, and, further, that all the musical practices of our current culture bore the influences (pro or con) of the ubiquitous worship songs of the hymnists who came before.

It saddened me, in the years that have followed this realization, that the great hymns of the past, once so universally known, were gradually being marginalized by newer songs, as the older hymns, which began to be seen as spiritually moribund and musically non-relevant, increasingly became unknown to younger believers, and lost to the culture at large, despite the fact that the influence of these hymns still undergirded that same culture.

I determined that arranging these hymns in more contemporary forms would revive interest by showing their intrinsic excellence in a newly refurbished light. In addition, the lives, challenges, and triumphs of these hymnists need to be made known to Christians today, as a context for their songs. And, with Reliquarium, I began to do so, and am now involved in writing, teaching, and filming the results of these efforts, and have invited you, my friends old and new, to take part in this ongoing retrieval of our common Christian heritage.